“The discovery that mathematics is more than algorithms for calculating volumes of dirt or the magnitude of taxes is credited to a lone Greek merchant-turned-philosopher named Thales a bit more than 2,500 years ago.”

From Euclid’s Window, a book by Leonard Mlodinow.

Euclid’s Window is a brief and non too-serious history of the development of geometry, that highlights conceptual breakthroughs from Thales (5th century BC) to the emergence of M-theory at the end of the 20th century. The book is divided into five stories — Euclid’s, Descartes’s, Gauss’s, Einstein’s and Witten’s — but also emphasizes that none of those trailblazers lived in a vacuum.

Euclid’s Window is a brief and non too-serious history of the development of geometry, that highlights conceptual breakthroughs from Thales (5th century BC) to the emergence of M-theory at the end of the 20th century. The book is divided into five stories — Euclid’s, Descartes’s, Gauss’s, Einstein’s and Witten’s — but also emphasizes that none of those trailblazers lived in a vacuum.

The author begins with a claim that “Euclid was a man who possibly did not discover even one significant law of geometry. Yet he is the most famous geometer ever known and for good reason.” Then he goes on to describe how ancient Greeks transformed the practical knowledge of earlier Egyptian and Babylonian mathematicians into a much broader understanding of “earth measurement”, or in Greek, geometry. The former worked to find solutions to specific problems. Thales and his successors saw beyond particularities. They introduced abstract concepts that apply to many unrelated circumstances. Euclid’s story begins with Thales and Pythagoras, and continues after the introduction of Euclid’s famed postulates. For example, in 212 B.C., Erasosthenes, the chief librarian of Alexandria, calculated the circumference of the earth by employing geometry. Surprisingly, his calculation was so accurate that his error was within 4% of the correct value!

The second story is that of René Descartes, a French philosopher from the seventeenth century. Descartes’s greatest contribution to geometry is connecting it to algebra. His discovery replaced descriptions of curves like circles and ellipses with equations, and his coordinate system revolutionized how distances between points in space are recorded. Historians of science can probably explain why it took so long for mathematicians to start using algebraic equations to describe curves given that scientists, well versed both in Geometry and in Algebra, flourished during the middle ages. Euclid’s Window does not go into such speculations, but it mentions some of the challenges Descartes faced, before, during and after he developed his new method to describe positions in space in terms of algebra.

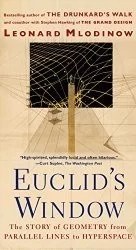

Mlodinow calls his next choice, the discovery of non-Euclidean geometry, “the greatest revolution in Geometry since the Greeks.” Non-Euclidean geometry is much harder to visualize than Euclidean geometry, as it’s not a concept readers encounter in everyday life, or are familiar with from high school math. For over 2000 years many mathematicians deemed that Euclid’s parallel postulate (for any given line, only one parallel line can be drawn through any given external point) was not as intuitive as his other assumptions. However, all attempts to prove it failed. It took the genius and the self-confidence of Gauss to make the leap to a different geometry. Gauss did not show that Euclidean geometry is wrong. Instead, he made a different assumption and discovered a new geometry that describes a curved space where the sum of the three angles of a triangle is less than 180º. In curved space, for any given line, there are not just one, but many parallel lines through any given external point.

Gauss’s idea that the curvature of a space could be studied solely on the surface itself is even less intuitive, but Mlodinow uses his sons (repeated characters in the book) to illustrate what this means. Gauss’s final stroke of genius was to compel Riemann to work “On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Foundation of Geometry.” Riemann’s consequent work expanded Gauss’s curved spaces, and set the stage for Einstein’s general theory of relativity which entwines physical concepts like energy, mass, and momentum with space itself.Image from Feymann Lectures

Gauss’s idea that the curvature of a space could be studied solely on the surface itself is even less intuitive, but Mlodinow uses his sons (repeated characters in the book) to illustrate what this means. Gauss’s final stroke of genius was to compel Riemann to work “On the Hypotheses Which Lie at the Foundation of Geometry.” Riemann’s consequent work expanded Gauss’s curved spaces, and set the stage for Einstein’s general theory of relativity which entwines physical concepts like energy, mass, and momentum with space itself.Image from Feymann Lectures

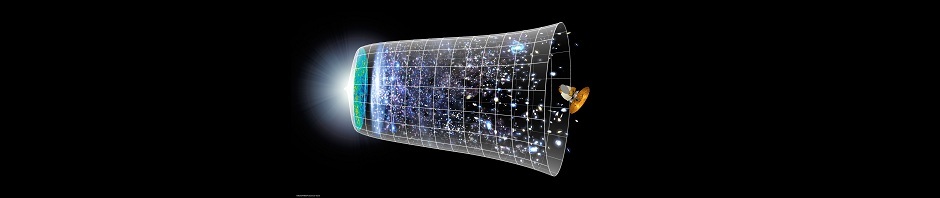

Einstein’s story is the best known one, so I won’t repeat any of it here.

The last story, that of the string theorists, stands out in many ways. First, unlike the previous stories, here the author personally knows the protagonists and had a front seat view of the evolution of their work. Second, I know nothing about M-theory, but the author claims that its predictions are relevant for physics. It seems to me that if there was observational evidence for any incarnation of string theory, the news would have spread beyond the small community of mathematicians and theoretical physicists. A quarter of century has passed since Euclid’s Window was published, yet I did not hear about any such observation.

In all, I enjoyed reading Euclid’s Window. I found the book easy to read, despite its topic (geometry was my least favorite math subject in school). And what is rarer, it made me want to continue to read to the end. I recommend this book to those who want a glimpse at the evolution of geometry’s fundamental ideas, who are curious about scientists’ understanding of what space is. The book does not assume that readers have a mathematical background, and does not offer scientific rigor. I think that it makes the book not only comprehensible, but interesting. In that, I completely disagree with the distinguished mathematician who opened his review of the book with: “This is a shallow book on deep matters, about which the author knows next to nothing.” Mlodinow’s scientific career shows that he does understand something about geometry. He could have sprinkled his book with expressions like “conformal invariance of Euclidean geometry” and “a Riemannian manifold is Euclidean if and only if it is flat.” Such additions were unlikely to increase readers’ understanding of these “deep matters”. But maybe then the reviewer would have omitted some of the accusations that “the author shrinks from nothing in his desperation to be ‘readable and entertaining’”.

I do have one last nitpick: Whoever edited the book shouldn’t have missed the incorrect attribution of “To see a world in a grain of sand” to Keats. Obviously, it’s not a blasphemy to confuse between two romantic English poets, but only Blake could begin the Augeries of Innocence with

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

To me, writing that the “poetry fits the mathematics,” adds insult to injury. I appreciate Mlodinow’s explanations of Euclid’s, Descartes’s, Gauss’s, Einstein’s and Witten’s groundbreaking discoveries. Trailblazers, however, are not the sole prerogative of mathematics and sciences. William Blake was a visionary poet who elevated imagination and abhorred logic. As his song attests, he perceived curved space and time that ticked differently. As Blake’s poem preceded Gauss’s discovery of curved spaces and that much later work that connected space with time, I don’t think that Blake would have appreciated the arrogance of scientists who fit his song into mathematics. Maybe Blake would not have objected if the conclusion was that math fits poetry.

A fragment of the second book of the Elements of Euclid. Source: Wikipedia

A scene from Macbeth, Banquo’s Ghost by Théodore Chassériau 1855,

A scene from Macbeth, Banquo’s Ghost by Théodore Chassériau 1855,

Mountain Laurel in our garden

Mountain Laurel in our garden Blackberry blooming in our garden

Blackberry blooming in our garden Hybrid tea rose in our garden

Hybrid tea rose in our garden