“From the time of Newton, leading scientists had believed that the universe was governed by mechanical laws: material objects held energy and inflicted forces. To them, the surrounding space was nothing more than a passive backdrop. The extraordinary idea put forward by Faraday and Maxwell was that space itself acted as a repository of energy and a transmitter of forces: it was home to something that pervades the physical world yet was inexplicable in Newtonian terms – the electromagnetic field.”

FARADAY, MAXWELL, and the ELECTROMAGNETIC FIELD, by Nancy Forbes and Basil Mahon.

As the title of the book suggests, FARADAY, MAXWELL, and the ELECTROMAGNETIC FIELD are the three main characters. Michael Faraday was the brilliant experimentalist who first came up with the concept of the electromagnetic field. James Clerk Maxwell was the genius theoretician who formulated the laws of electrodynamics and showed that electromagnetism and light were manifestations of the same phenomena. The discovery of Electromagnetic Field has transformed our world.

The first chapter introduces a thirteen-year-old Michael Faraday, an apprentice bookbinder with a keen interest in how electricity works. In an astounding turn of events, young Faraday, who had little formal education, became an assistant to Humphry Davy, the greatest man of science in Europe. Reading on, one gets a glimpse into the new world Faraday joined – he met with Europe’s leading scientists, and yet Davy’s wife treated him like a servant, because of the British class system. The real story, however, begins after a concise survey of the history of electricity and magnetism since the 1600s. Most notable were the discoveries made by Ørsted and Ampère, that related between magnetism and electric currents – they changed the course of Faraday’s career.

The book describes and explains Faraday’s groundbreaking experiments, and overviews the painstaking work he did. It points not only at his famous successes, but also to his failures. Most interesting is the way it tracks the slow evolution of Faraday’s notion of lines of force. Knowing what we know today, it is weird that

“Despite the universal acclamation of Faraday’s scientific work, his greatest achievement had been largely ignored during his lifetime, and was only beginning to surface at the time of his death.”

But it’s interesting to find out why Faraday’s lines of force were not taken seriously by his contemporaries, who adhered to the widely accepted Newtonian concepts of action at a distance. Moreover, one starts to see why it took the genius of Maxwell to fully understand Faraday’s greatness.

As the book’s focuses on James Clerk Maxwell, it shifts to the world of lairds in early Victorian Scotland. Unlike Faraday, who barely had any formal education, young Maxwell was educated at Edinburgh Academy, one of the best schools in Scotland. He published his first mathematical paper at the age of fourteen. At nineteen, Maxwell was already an experienced scientific experimenter and had published three mathematical papers. He was ready to leave Scotland for “the society and drill” of Cambridge.

The portrayal of Maxwell’s years at Cambridge pictures the world of bright, privileged, and often ambitious young gentlemen. It also gives insight into how the prodigy boy became one of the greatest physicists of all time. An illuminating example is Maxwell’s introduction to Faraday’s work:

“Scanning the books and papers that Thomson had recommended, Maxwell soon saw that the state of knowledge about electricity and magnetism was unsatisfactory. Much had been written, but each leading author had his own methods, terminology, and point of view. All the theories except Faraday’s were mathematical and based on the idea of action at distance. Their authors had largely spurned Faraday’s notion of lines of force because it couldn’t be expressed in mathematical terms,…”

Contrary to what one might have expected, Maxwell, the natural mathematician, was drawn to work on Faraday’s concept.

It took nine years for Maxwell to develop his theory. Nancy Forbes and Basil Mahon take the reader through Maxwell’s personal and scientific milestones during that period. What I learned is that Maxwell was shunned repeatedly by Scottish universities even though he was one of the most prominent figures in nineteenth century science. That makes one wonder, what would physics have looked like if Maxwell was not independently wealthy, and couldn’t work on his magnum opus at his estate Glenlair?

The authors discuss the various steps Maxwell took while developing his ideas, and use diagrams to visualize his process of thinking. They do not dwell on the mathematics, but describe the results summarized in Maxwell’s equations, then explain what was so revolutionary about the new theory.

The last part of the book is about the evolution of the theory of electromagnetism after Maxwell.

“In the story of electromagnetic field, Maxwell was a lone actor in his time, just as Faraday had been in his. Not until the following generation did anyone else truly understand what Faraday and Maxwell had been trying to tell them. The way was then led by a small band of individuals…”

Not quite surprisingly, the story goes on, and one meets the who’s who in the physics of the early twentieth-century.

Do I recommend the book?

Yes. The authors’ admiration for Faraday and especially Maxwell shines through the pages, and it doesn’t spoil the reading. After all, these two men were giants, and also well-grounded and very decent human beings. Some of the descriptions of Faraday’s experiments and Maxwell’s “cells” and “wheels” were too lengthy to my liking, but reading about the incubation and the evolution of one of the most fundamental concepts in physics more than compensated for it.

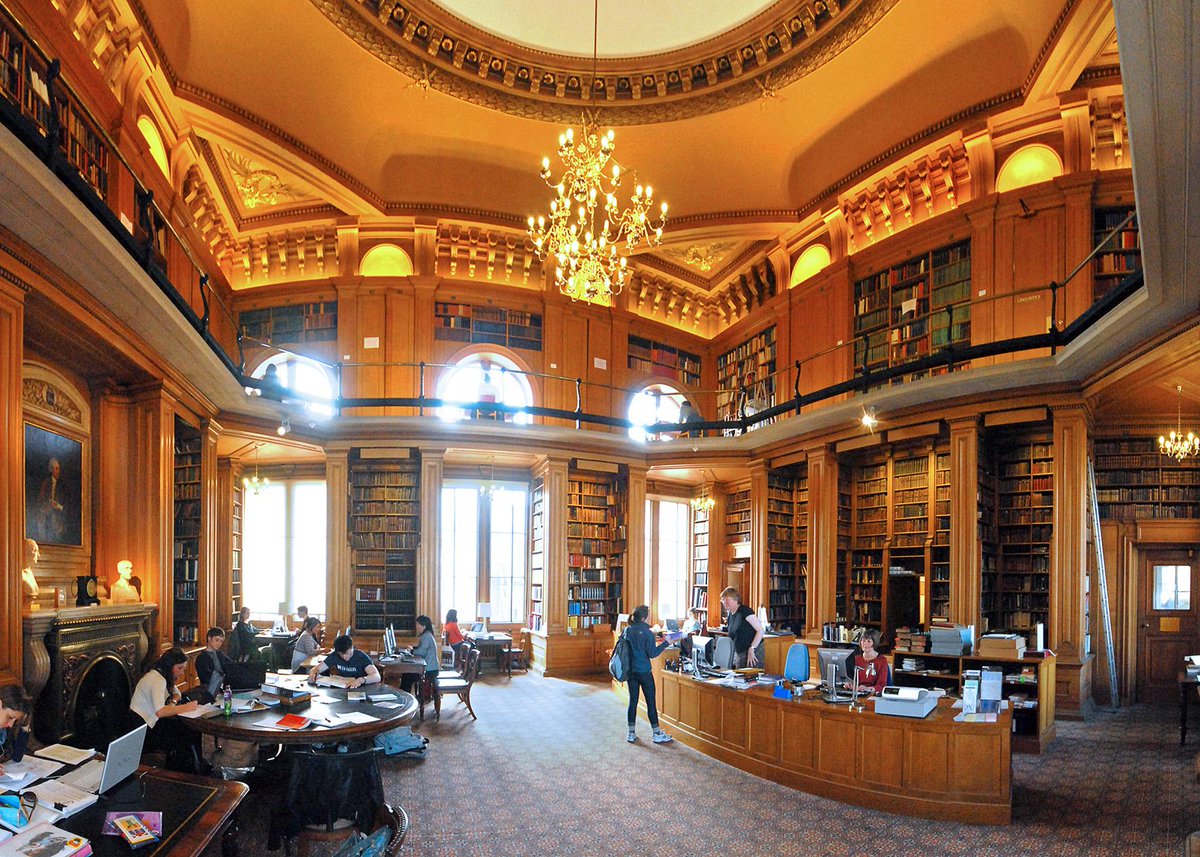

The Baroque library hall inside Clementinum, Prague, Czech Republic

The Baroque library hall inside Clementinum, Prague, Czech Republic